A recurring problem: trying to write about a multi-season TV show. I’ve written elsewhere on this blog about how TV shows are generally trickier subject matter than movies—more diffuse, more erratic—and those problems are compounded when you’re dealing with three or four or more seasons. Whether trying to catch up—and I can only get through something at a somewhat accelerated pace; I think Mad Men is the only show I’ve ever truly binged in the understood sense of the word—or faithfully keeping up over a number of years, by the time I finish, everything tends to blur together. I probably should have posted something on The Handmaid’s Tale halfway through S2, when X-Ray Spex ended an episode with what was the first really startling musical moment for me, but I also thought that maybe that signaled a new and more important role for music in the show, so I waited. And here I am now, trying to piece together a show that, with S4 just about to begin, sometimes feels like it has wandered far afield from where it began.

I’m not sure if the makers of The Handmaid’s Tale have ever really figured out how prominent they want pop music to be. Every now and again, it’s front and center, but then two or three episodes will go by with nothing of consequence, occasionally with nothing at all. Which is fine; I can appreciate how Mad Men’s rigid episode-ending-song format became tiresome for some viewers. In any event, I’m glad I waited—X-Ray Spex was just prelude to an even greater song cue down the road.

I kept thinking about The Leftovers as I made my way through The Handmaid’s Tale. That similarly had an on/off switch when it came to its soundtrack, and the shows are also linked by the presence of Ann Dowd, memorable in both playing characters whose cruelty is rooted in an anguished past revealed through flashback. And that’s where the two shows really converge: there’s the past and there’s the present, and between them sits a cataclysmic, world-altering event. When I rewatched The Leftovers a year ago, I mentioned on a message-board how eerily it resonated with the then-nascent pandemic. Seemingly stuck in exactly the same place today—but infinitely more exhausted—I’d say the same of The Handmaid’s Tale. And I almost uniformly love the flashbacks to the before world: the banter between June and Luke and Moira, Emily teaching cellular biology back in university, June’s activist mom; even Aunt Lydia is granted a night of karaoke and a glimmer of romance, maybe the only moment of grace for Ann Dowd in either The Handmaid’s Tale or The Leftovers (also an instant addition to the Movie-TV Karaoke Canon I’m presently developing).

The problem I had as things moved along—I’ll get to the music in a moment—was what felt like endless reversals. June: compliant and demoralized one moment, feisty and ready to start a revolution the next, then back and forth a dozen more times. The June and Serena relationship: bitter adversaries one episode, seemingly on the verge of an alliance the next, then back and forth a dozen more times. I asked someone on the message board at one point if the show had moved beyond Margaret Atwood’s novel, and the reply was that had already happened in the first season; it seemed clear to me that they were just making it up as they went along, doubling back on themselves constantly.

And once Bradley Whitford’s Joseph Lawrence entered the picture towards the end of S2, I basically lost any overriding semblance of why the things that were happening were happening. I don’t think I’ve been as perplexed by a TV character since Patricia Clarkson’s Jane Davis in House of Cards, and he seemed to fundamentally change something in the show’s calculus. Soon into S3—I was convinced I’d fallen asleep one episode and missed some crucial transition—June was a behind-the-scenes powerbroker, arranging meetings and bending events to her will, with Lawrence wandering in and out some elliptic, acerbic commentary. Some of it very funny, I should add—like Jane Davis, he operates in some universe entirely his own. (Whitford’s resemblance in both voice and manner to Dennis Hopper helps.) Where it all goes from here, I don’t know. I’ll be watching.

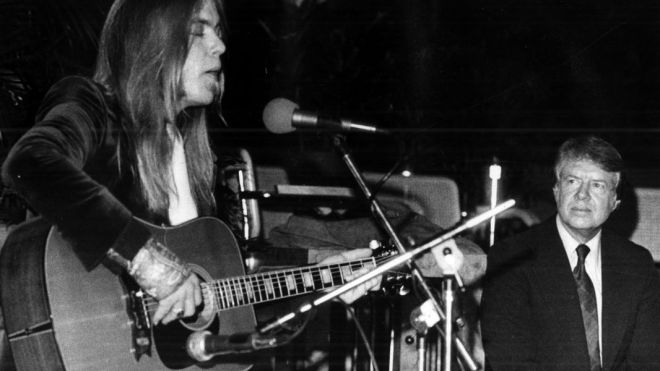

I haven’t read Margaret Atwood’s novel—there should be a “I haven’t read the novel” keyboard shortcut for me—but, first published in 1985, I’m guessing it was originally intended to be as much a response to the emerging “Moral Majority” in Reagan’s America as it was a work of Feminism. The show is tilted towards the latter, perhaps nowhere more militantly than when “Oh Bondage! Up Yours!” closes out S2’s “First Blood.” Commander Waterford is addressing a roomful of dignitaries at the opening of the Rachel and Leah Center, designated to be a future training ground for handmaids; out form among those in attendance, lined up at the back of the room, Ofglen #2 (Lillie) emerges with a bomb in hand, which she detonates as the rest of the handmaid’s flee in slow motion. Cut to black and Poly Styrene: “Some people think little girls should be seen and not heard/But I say…”

High marks just for its inclusion—it’s hard to adequately convey the monumental thrill of Poly Styrene’s voice in any context, but especially if explosives and carnage are involved (death toll: 31 handmaidens, unfortunately, but also 26 commanders), and that’s why I’m singling it out. When I stepped back and thought about the scene later, though, they may have missed the more obvious way to incorporate the song, more like how Olivier Assayas used “Sonic Reducer” in Carlos: start it up as soon as Ofglen pulls out the bomb, letting the song choreograph the chaos rather than just comment on it. (Synchronicity: when writing about Carlos in the book version of this blog, I said of the “Sonic Reducer” scene that “If you could get Patti Smith’s ‘Gloria’ onto film, it’d play out like this.” In a Tunefind piece on the best musical moments in The Handmaid’s Tale, the show’s music supervisor Maggie Phillips says that they were originally going to go with “Gloria” for the bombing scene.)

Lots else worthy of comment before and after “Oh Bondage!”, but this is where waiting has reduced me to a WhatSong-assisted checklist:

- “You Don’t Own Me” to finish the first episode; a marker for everything that follows, also a bit too familiar

- “White Rabbit” as June and Waterford enter Jezebel’s, Gilead’s version of Twin Peaks’ One-Eyed Jacks (The Handmaid’s Tale often plays around with pop-culture history, the Jaws quote that ends one episode the most obvious example; June’s stated preference for the second Aliens film over the original, the most knowing)

- “American Girl” to end S1 (a nod to The Silence of the Lambs, I would think)

- June and her mom singing along to “Hollaback Girl” in flashback (another missed chance: they should have brought it back for the end credits)

- Iris DeMent’s “My Life” for a post-bombing memorial ceremony; a friend told me to watch out for a particularly stunning musical moment before I began the series, and this was it—good, for sure, but I’m not quite the Iris DeMent fan he is (more Leftovers overlap, too)

- “Venus,” Shocking Blue version, at a moment when June and Serena appear to be in cahoots for good

- “Itchycoo Park,” with Commander Lawrence in his office doing whatever the hell he does in there

- “Burning Down the House” to end S2, June going all in on revolution once again (the seventeenth time, I think, by that point)

- Roy Harper’s “How Does It Feel” as Serena pulls a Norman Maine but has second thoughts—this was the one great song I discovered via the show

- “Cruel to Be Kind,” Lawrence and his wife listening to music, part of an entire Love Is a Mix-Tape episode

- “Everyday” to end S3’s “Household,” what has to be a Mad Men reference (I haven’t said anything yet about Elisabeth Moss as June: she’s phenomenal in S1, then gamely does battle with the show’s “Really, again?” wheel-spinning after that)

- “Que Sera Sera,” Doris Day version, to finish the episode after the next—pure Mad Men*

And on and on—laying it all out in one place, I suppose pop music is a lot more central to the show than I originally indicated. (Yet a few episodes have no songs, and many were limited to one or two not worth mentioning.) Probably the oddest musical interlude was Belinda Carlisle’s “Heaven Is a Place on Earth,” where June accompanied the song with a running commentary on the lyrics, occasionally singing along herself (even though it was used non-diegetically). Someone else could make this whole post just about that one episode. I’d have to like the song more, though—it’s okay.

Very early in S1, I found myself wondering “What kind of soundtrack would most fit this show?” I settled on something I first came into contact with when I started downloading everything in sight from Soulseek almost 20 years ago: British psych-folk from the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Not entirely new to me—I’d had the Incredible String Band’s The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter since I discovered it as a teenager in a pile of records we kept in the basement; and I loved a few Fairport Convention songs, of course—but bands like Paramater and the Moths and the Trees were. Roy Harper is tangential to the genre, but “How Does It Feel” has some of the same feeling I get from those bands, and from Bert Jansch, too: Barry Lyndon by way of the Jefferson Airplane, hippie reverie that sounds a thousand years old.

As does, even more tangentially, Kate Bush’s “Cloudbusting,” which closes S3’s “Liars.” It’s the morning after June’s clandestine visit to Jezebel’s, where she was trying to make arrangements with Billy, the bartender, to sneak 52 children out of Gilead; cornered by Commander Winslow, they end up taking a room together and June proceeds to brutally murder him (fully justified in context). “Cloudbusting” starts up as some of the Marthas back at Jezebel’s methodically go about erasing all evidence of the murder (shades of Psycho), cleaning blood from the carpet, wiping down surfaces, disposing of the body. June, back home—Lawrence himself chauffeured her to and from Jezebel’s—wakes up, her face visibly bloodied, and she goes into the closet and selects her handmaid’s uniform for the day. “Cloudbusting” continues as we cut back and forth between June and the Marthas: stately, a little sad, but—those violins—suggestive that a corner has been turned, that something new is about to take shape. The scene ends with Lawrence’s best moment thus far—“They’ll be coming for us,” as he hands June a gun—followed by June sitting alone at the window.

I don’t know if I’ve ever had such an overwhelming sense of “Of course—that’s it, that one song is why this show exists” from any comparable moment in any other TV show I’ve written about here.** While there are indeed lyrical fragments scattered throughout “Cloudbusting” that suggest Gilead (“what made it special made it dangerous”; “a threat to the men in power”; “I can’t hide you from the government”), that’s secondary—until I looked them up, I’d never given a second thought to those lyrics. Even less consequential is the fact that “Cloudbusting” and Atwood’s novel appeared within a few months of each other in 1985. The connection is much deeper and more amorphous; it captures something intrinsic about the world of Gilead, of all those handmaids walking the streets silently, of June’s eyes in the many close-ups we get of her at key moments. I’d be hard-pressed to articulate exactly what that something is. It’s also—a lot easier to explain—made to order for the pandemic moment that drags on and on in our own world: “I just know that something good is going to happen/I don’t know when.”

Kate Bush is one of the 15 or so people up for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame this year. When I start mentally filling out the rough checklist I apply to nominees—clearly influential, sold a lot of albums, long career, a decent amount of critical attention—she’s a reasonable pick; there’s also that Creem/“Roadrunner”/Rock and Roll High School part of me that thinks, “Sure, and put in England Dan & John Ford Coley while you’re at it, we don’t want to miss anyone.” She’s not, in other words, someone I naturally gravitate to. But she’s also responsible for three songs I love (“Running Up That Hill” and “The Man with the Child in His Eyes” the others), and I’m surprised I never included “Cloudbusting” in one of the Top 100s I’ve assembled over the years. In part because of The Handmaid’s Tale, I definitely would today.

That’s it. Under his eye, praise be, blessed be the Fruit Loops.

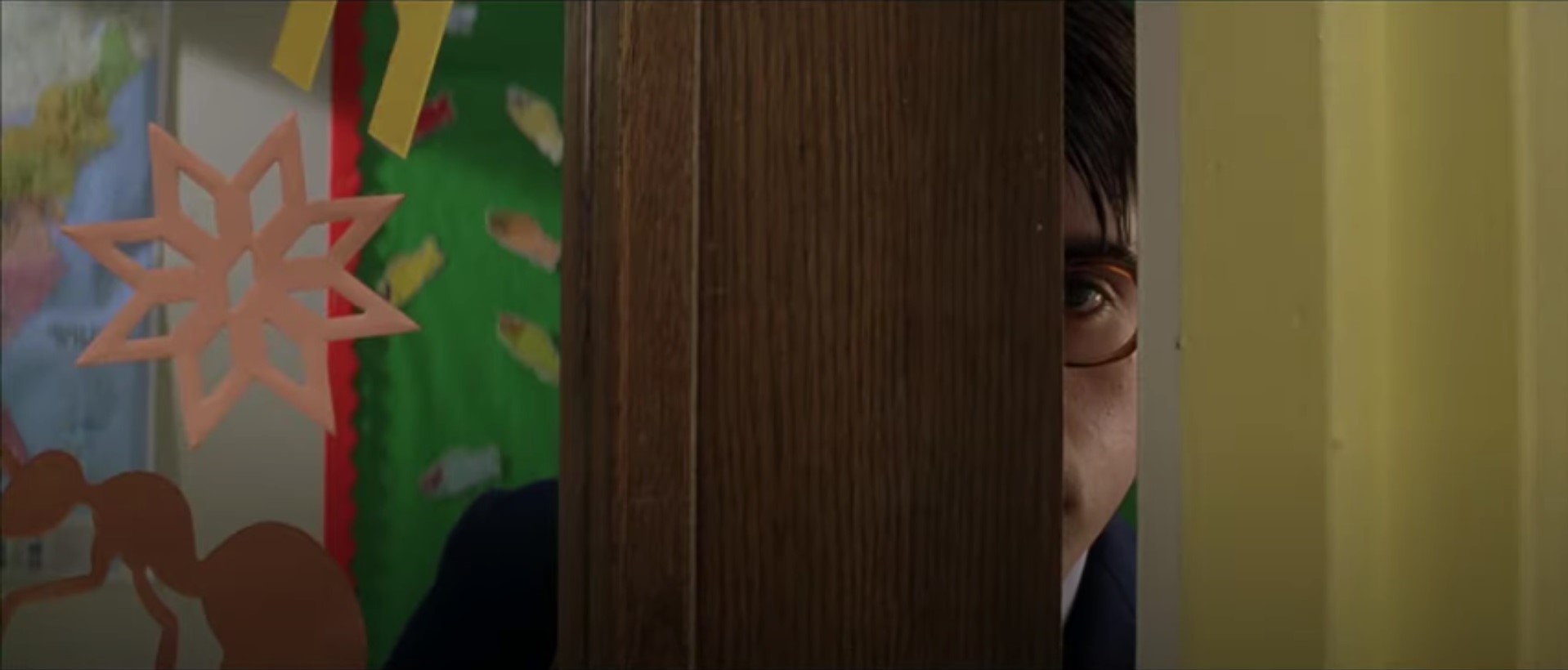

*I often thought of Peggy’s most iconic image from Mad Men—hung over and in shades, carrying her belongings into McCann Erickson—and also of my own favourite Peggy moment, at the elevator as “You Really Got Me” played, whenever June flashed her “I want to break things” look. Also worth mentioning: Emily (Ofglen #1) is played by Alexis Bledel, Beth Dawes on Mad Men, who in the unforgettable “Tomorrow Never Knows” collage drew a heart on her condensed car window.

**Bush showed up earlier, in the fake-hanging scene that opened S2, with “This Woman’s Work”; I don’t know the song, so it probably didn’t even register with me who I was hearing—if it had, I don’t think “Cloudbusting” would have resonated to the degree that it did.